Blackhall News

The curse of Colt Crag

At Blackhall Engineering Ltd, we provide our clients with peace of mind through the power of Valvology.

Article written in collaboration between Blackhall Engineering & Northumbrian Water.

Project Delivery Team

What is Valvology®? It is the science of flow control devices; valves that provide the ultimate in longevity, for any fluid, at any temperature and any pressure. It is the engineering of valves with personality, designed and manufactured here in the UK. In practice, it means guaranteeing a one-hundred-year design life in all of our valves, combining longevity with the best possible technical support and after sales service. Through Valvology®, we believe that we are quickly establishing ourselves as the most respected manufacturer of valves and service within the UK water industry.

Longevity is key, and whilst we are under no illusion about the cost of our valves when compared to those imported from abroad, the difference at Blackhall is that ours are delivered with the promise of ‘Valves for Life’. They are also made in Britain, which is something we’re immensely proud of. What this means is that our entire process, from consultation to final installation, is handled with the defence of British heritage and the protection of its environment in mind. After all, we are a British company manufacturing valves for British waterways – why would we not wish to protect them?

As an example, let’s explore a project we recently completed at Colt Crag Reservoir. Owned and operated by Northumbrian Water, the site is about 4km north of Colwell in the county of Northumberland, National Grid Reference NT 940 781.

As an example, let’s explore a project we recently completed at Colt Crag Reservoir. Owned and operated by Northumbrian Water, the site is about 4km north of Colwell in the county of Northumberland, National Grid Reference NT 940 781.

The reservoir is retained by an earth-fill embankment with a puddle core approximately 17.4m high and 189m long across the Dry Burn. It has a stated capacity of 4,848,214m3 and a surface area of 668,000 square metres, when full to its top water level of 201.57m above ordnance datum. It appears to have been constructed under the direction, and to the designs, of J. F. La Trobe Bateman, between 1878 and 1884. The contractor was William Rigby of Worksop. In April 1877, it was agreed to proceed with the reservoir proposed by Thomas John Beswick, with a capacity of I,068 million gallons at an elevation of 201.4m. Work commenced in 1878, with slips occurring in both faces of the Colt Crag embankment in October 1880 and March 1881.

The construction comprised an inner core adjacent to the puddle clay laid in 2ft (600mm) layers with poorer material flanking the core and laid in 2ft (120mm) layers, swept upwards from the centre. The slopes are I-in-2 downstream and 1-in-3 upstream. To counteract against slips, berms were formed on both faces, and modifications were made to the overflow channel. Leakage was quite severe, and a cut-off trench was constructed to the north, however it was not until 1912 that the leakage was made good by excavating a trench and filling it with concrete.

Due to the introduction of berms on both sides of the embankment, an upstream culvert (internally 2.4m in diameter at its upstream end, reducing to 1.45 metres near the valve tower) runs to the tower from a rectangular shaft measuring 3.35 x 2.44 x 6.4m deep. The culvert is built in massive masonry I.07m thick at the openings. Four openings in the upstream wall admit water to the shaft from the rockfill toe berm. The shaft itself has 2.3m2 timber struts spanning between the upstream and downstream walls.

A discharge culvert runs from the toe of the dam to the base of the valve tower. For about a third of its length from the portal, the circular culvert is of masonry construction around 2.36 metres in diameter, and thereafter of engineering brick construction, reducing in diameter.

Details of Modifications, Remedial Works and History

Repairs to the lower sluice and pitching were carried out in 1985. During the drawdown, the upstream culvert was also cleaned out. The wave wall was rebuilt and the crest road improved following the last inspection, and new levelling pins were installed in 1995. At the same time, a house was built on the valve shaft.

The valve tower was later overhauled in June 1997, which saw the removal of the existing line. The overhaul included the removal of existing concrete platforms and the provision of improved access, means of operation and maintenance for all valves. All metalwork was repainted, while both the metalwork and the internal brick surfaces were cleaned and repaired. The lining was reinforced with protected steel plates in the impact zone of the upper sluice, while a heavy-duty grid was provided at the sump.

Overflow

Comprising a long, low, broad-crested weir (40.54m long at a level of 201.57m Above Ordnance Datum (AOD)) the overflow discharges down a short flight of steps and into a shallow channel approximately 137m long, with a width of 6.09m.

Inlet and Outlet Pipework and Valving Arrangements

The valving arrangements of Colt Crag are enclosed in a valve tower 1.83m in diameter, constructed of brickwork and set into the embankment upstream of the puddle core. At the time of construction, the valve tower was reinforced with four additional internal brick rings. However, 130 years after the original construction, there is a reported inclination towards the reservoir of about 0.80.

There is an upper and lower draw-off sluice (both 2ft 8" wide x 3ft 2" deep) discharging into the valve shaft and then to the discharge culvert. The lower sluice is part of a large cast iron plate. On the bulkhead, there are two additional 150mm diameter outlets, each provided with two sluice valves mounted onto the bulkhead. Both sluices are operated from headstocks at the top of the valve shaft.So where do we come in? Due to the historic issue of the lean, Northumbrian Water had much concern over the ability of the drawdown valves. To quote from historical records of 1890, “a principal fault in the embankment was movement in the valve tower, due to the unequal horizontal thrust imposed upon it as a result of its location within the embankment.” Despite being measured 14 inches out vertically, no steps were taken to rectify it. The principal problem that resulted from this, was an adverse effect upon the operation of the sluices, about which complaints later arose due to them requiring four hours’ work to open and close!

In fact, during the NWL annual valve testing of 2020, it was noticed that the headgear had become fractured and dangerous to operate, the valves having no suitable method of restraining the loads imposed on them during operation. In the first instance, Northumbrian Water contacted Blackhall Engineering, to see of a suitable, long-term solution might present itself to remedy this long-standing historical defect, both for now, and for future generations.

The lean became severe enough to render the main valves inoperable. Faced with the considerable expense of rebuilding the tower, our customer decided to call in Blackhall, to see if an alternative might present itself. At this point, our Service Director, Dave Richmond says that in all his years of experience, he had never come across such a failure mode! That said, we were quickly able to come up with a neat solution, which was duly proposed and happily accepted by the customer.

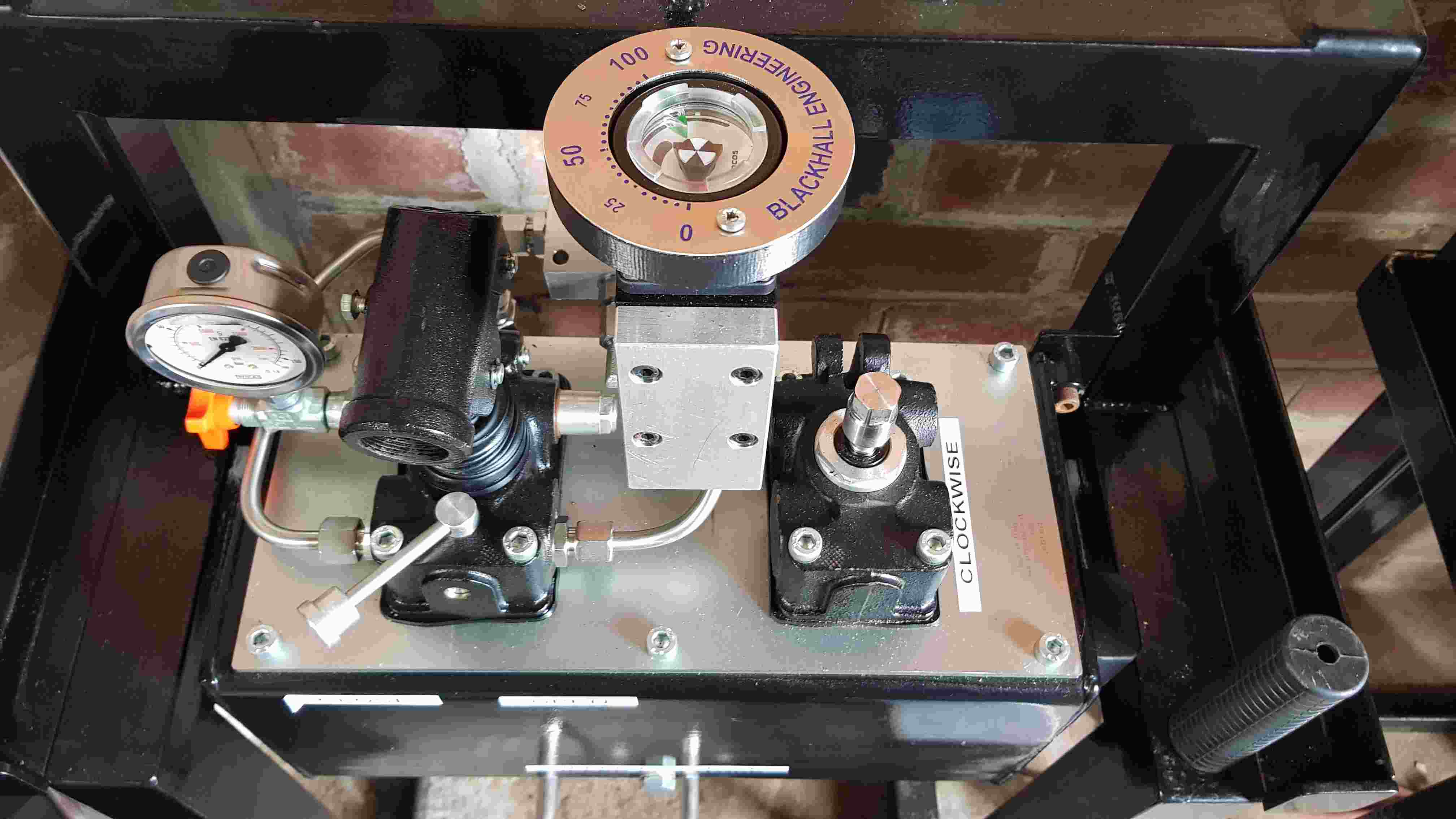

Upon visiting the site, we identified that the main valve pedestal had cracked due to excessive movement, which in turn had caused the operating gear – which ran the full height of the tower – to bend and eventually seize completely. Our solution was quickly drawn up into an initial 3D design, which was submitted and accepted without issue, giving us the green light to make a start. So far so good.

Upon visiting the site, we identified that the main valve pedestal had cracked due to excessive movement, which in turn had caused the operating gear – which ran the full height of the tower – to bend and eventually seize completely. Our solution was quickly drawn up into an initial 3D design, which was submitted and accepted without issue, giving us the green light to make a start. So far so good.

Things started to get interesting, however, when it came to making good on the proposal, at which point the site team found themselves needing to constantly monitor the tower for structural movement. Built from bricks manufactured in the 19th century, we were unable to rely upon their structural integrity, nor that of the conventional fixings that we would otherwise use. Instead, we had to beef up the design, all the while diligently testing the pull strength of the fixings. In order to prevent failure of the ageing internal brickwork, the bracket design for the hydraulic cylinder was critical, as was the alignment of spindles through the bracket, connecting the new cylinder to the existing valve and ensuring a successfully operating valve. Utilising a combination of tried and tested plum line methods and modern laser positioning, alignment was achieved, thus preventing side-loading to the cylinder rod. The specialised ‘Hilti’ fixings and mountings that we used were positioned precisely in the centre of the bricks, thus maximising the loading capability. Once the fixings were in place, vertical supports were slotted into the framework for ease of installation, providing the site team with a degree of adjustability.

Another challenge was the complex task of lifting the parts into place. In fact, our lifting partners, Calder Lifting, were called in to design and manufacture a bespoke lifting gantry especially for the job, which was installed and locally tested in order to establish safe working limits. We used the gantry to remove the old, warped spindles and lower new cylinders into place, mounting them onto the original valves without the need for extension rods. Even with the gantry in place, the internal diameter of the tower – just 1.8m – meant that the removal of the existing spindles and the installation of their replacements was challenging, to say the least. Not to mention the fact that all parts had to be traversed across a narrow bridge, which itself had to be load tested for safety.

The bridge alone was but a flavour of the poor site access we would experience at Colt Crag. With no defined highway, 4x4 vehicles were essential, and with weather issues ranging from falling trees in severe winds to relentless deluges of winter rain, even they struggled to contend with the deteriorating terrain. In short, we had our work cut out. But a deadline is a deadline, and with the non-negotiable completion date of January 2022 looming, we forged ahead, nose to the grindstone. "It certainly was a test of endurance and perseverance," says Dave, whose tenacious team were able to complete the job on time. Crucially, they were able to do so with minimum disturbance to the site’s Victorian heritage and, thankfully, without needing to call on the MRS Training & Rescue team, who were on hand just in case. Still, says Dave: "We would appreciate a summer slot next time!"

The bridge alone was but a flavour of the poor site access we would experience at Colt Crag. With no defined highway, 4x4 vehicles were essential, and with weather issues ranging from falling trees in severe winds to relentless deluges of winter rain, even they struggled to contend with the deteriorating terrain. In short, we had our work cut out. But a deadline is a deadline, and with the non-negotiable completion date of January 2022 looming, we forged ahead, nose to the grindstone. "It certainly was a test of endurance and perseverance," says Dave, whose tenacious team were able to complete the job on time. Crucially, they were able to do so with minimum disturbance to the site’s Victorian heritage and, thankfully, without needing to call on the MRS Training & Rescue team, who were on hand just in case. Still, says Dave: "We would appreciate a summer slot next time!"

A huge thank you has to go to both ESH Stantec & Northumbrian Water for their support, dedication & collaboration in helping to make this project a great success.

Send Us Your Enquiry